From the start, his mother knew this was no ordinary child. When he was forty days old, Mary and Joseph, his earthly father, took him to the Jewish Temple for Presentation. There the mysterious old Simeon made his devastating prophecy to Mary: that the baby was “a sign of contradiction, while a sword will pierce your own soul”. And thus in the beginning was the end foreseen…

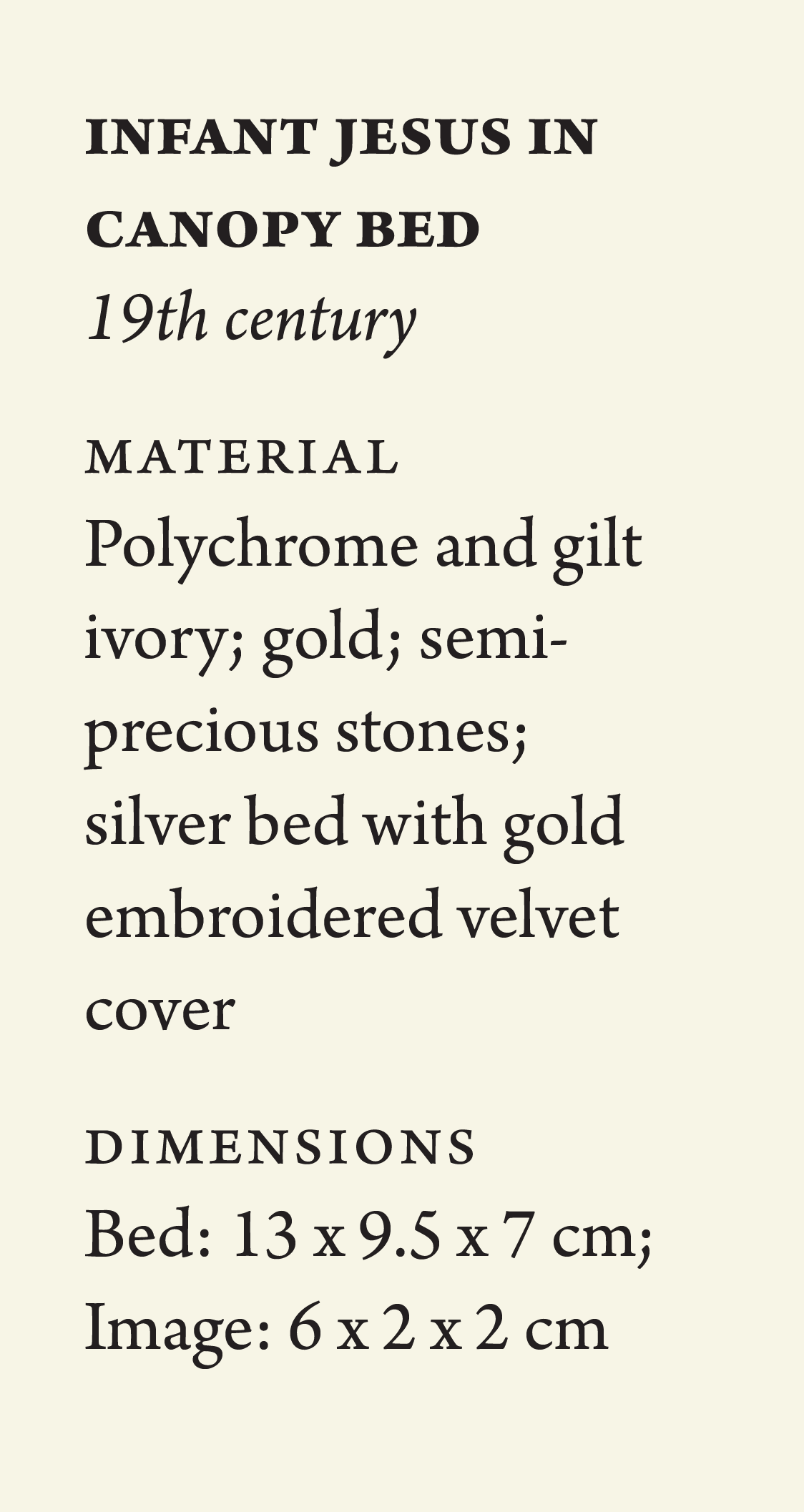

The Infant Jesus in his crib was a popular devotional object in 15th and 16th century Europe. It was part of a woman’s dowry, and also given to nuns taking their vows. Richly decorated cribs came to form part of the nativity scene at Christmas in Jesuit churches in the second half of the 16th century in Europe. But the first time such a scene was celebrated was by St. Francis of Assisi in 1223, inspired by a visit to the Holy Land, and greatly moved at beholding Christ’s traditional birthplace.

Another exquisite example of this type of object, a Repos de Jésus, is a 15th century wood, polychrome and gilt silver reliquary cradle from Brabant (southern Netherlands) that can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

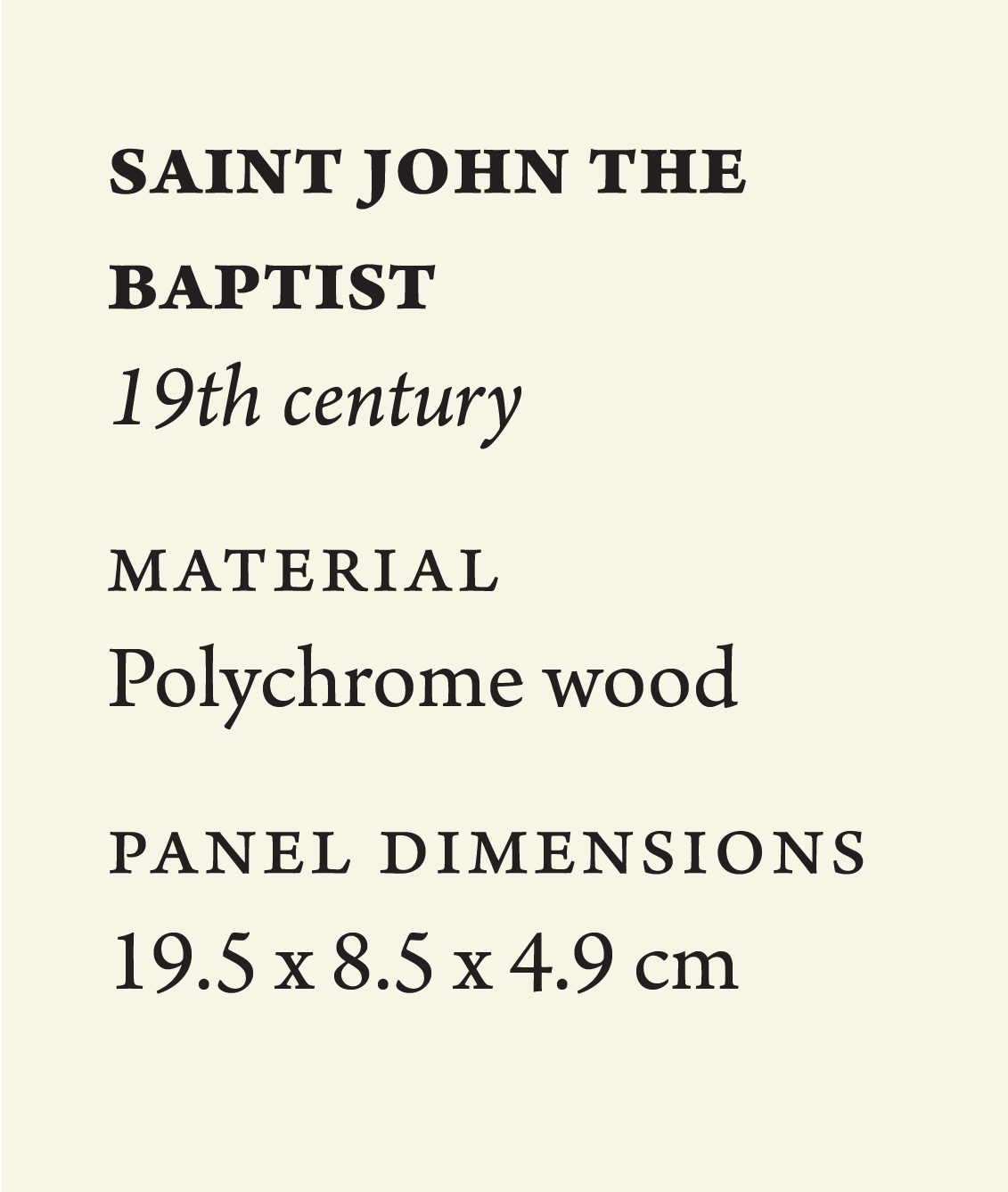

It was his cousin John who baptised Christ in a place east of the River Jordan, having foretold the arrival of someone “more powerful” than himself. And this John knew, babe unborn, when the Virgin Mary, his mother, Elizabeth’s kinswoman, came to visit her before his own birth. Perceiving the Saviour’s Mother before him, John had leapt with joy in his mother’s womb.

And now as Jesus emerged from the waters, John saw the dove-shaped Holy Spirit descend on his cousin and a heavenly voice declare him the Son of God. “Behold the Lamb of God,” cried out John, and at once his own disciples, for a holy preacher was he, became Christ’s followers. Thus did John prepare Jesus, then thirty years old, to begin his own public ministry.

The mystical connection between the cousins was celebrated as early as the 5th century CE in Christian art. The most famous painting on the subject is The Baptism of Christ (c. 1448-50) by the Italian Renaissance master Piero della Francesca, held at the National Gallery, London.

Jesus the ‘Rabbi’ (as some called him) spoke of God’s love through sermons and parables. Word of his wisdom and miracles grew, and people flocked to him. Then Jesus began his fateful journey towards Jerusalem, even as he knew it was the beginning of the end. As he passed through the place of his own baptism, the crowds swelled, hearing of how he had raised Lazarus from the dead...

At last Jesus made a triumphant entry into Jerusalem, hailed by the crowds as Messiah. Going straight to the Jewish temple, he threw out the traders and money changers there, and began to preach his truth. At this, the Jewish priests, already angry and alarmed at the crowds Jesus had attracted, confronted him. ‘By whose authority do you speak here?’ they demanded.

Then did the story quickly, alas, tragically, unfold. Jesus, betrayed by his own people, and tried for blasphemy by the priests, was arrested by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate.

Christ’s Passion (in Latin, ‘suffering’), with its many pain-filled scenes, was a popular subject in Christian art, in both painting and sculpture. The images were meant to allow the faithful to suffer alongside their Saviour, and thus be redeemed from their sins.

But Pontius Pilate, on speaking to Jesus, found no crime by Roman law. Yet was Jesus scourged, and yet Pilate found no fault, bringing him before the crowds. The Roman soldiers had mockingly robed him in royal purple, for was he not the King of the Jews? On his head was a crown of thorns, and in his hand a green reed, like a sceptre. Pilate knew Jesus was guilty of no crime that deserved crucifixion, the harshest Roman punishment. ‘Behold the man!’ he said, pointing to Jesus, his frail body lacerated and bloody, hands and neck bound with rope like a common criminal. ‘What would you have me do with him?’ ‘

Crucify him!’ roared the crowd that had just days earlier hailed Jesus as the Messiah. And so Pilate handed him over to the soldiers.

The Ecce Homo (in Latin, ‘Behold the man!’) image developed c. 1400, possibly in Burgundy in France. From the 15th century onwards, Christ was shown alone, as here, his eyes compelling the viewer to share in his suffering. Also called Man of Sorrows or King of the Jews, the theme took on great significance during the Counter-Reformation. It was a common subject in paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and in Baroque sculpture.

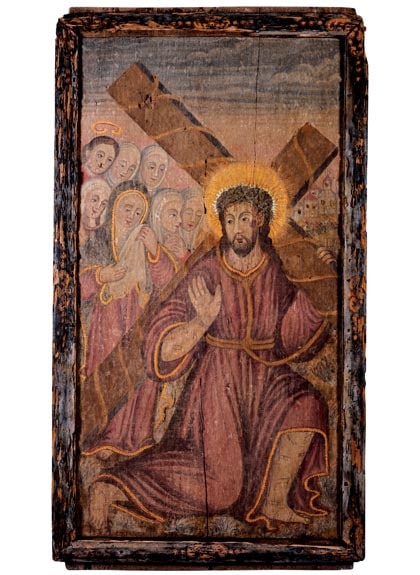

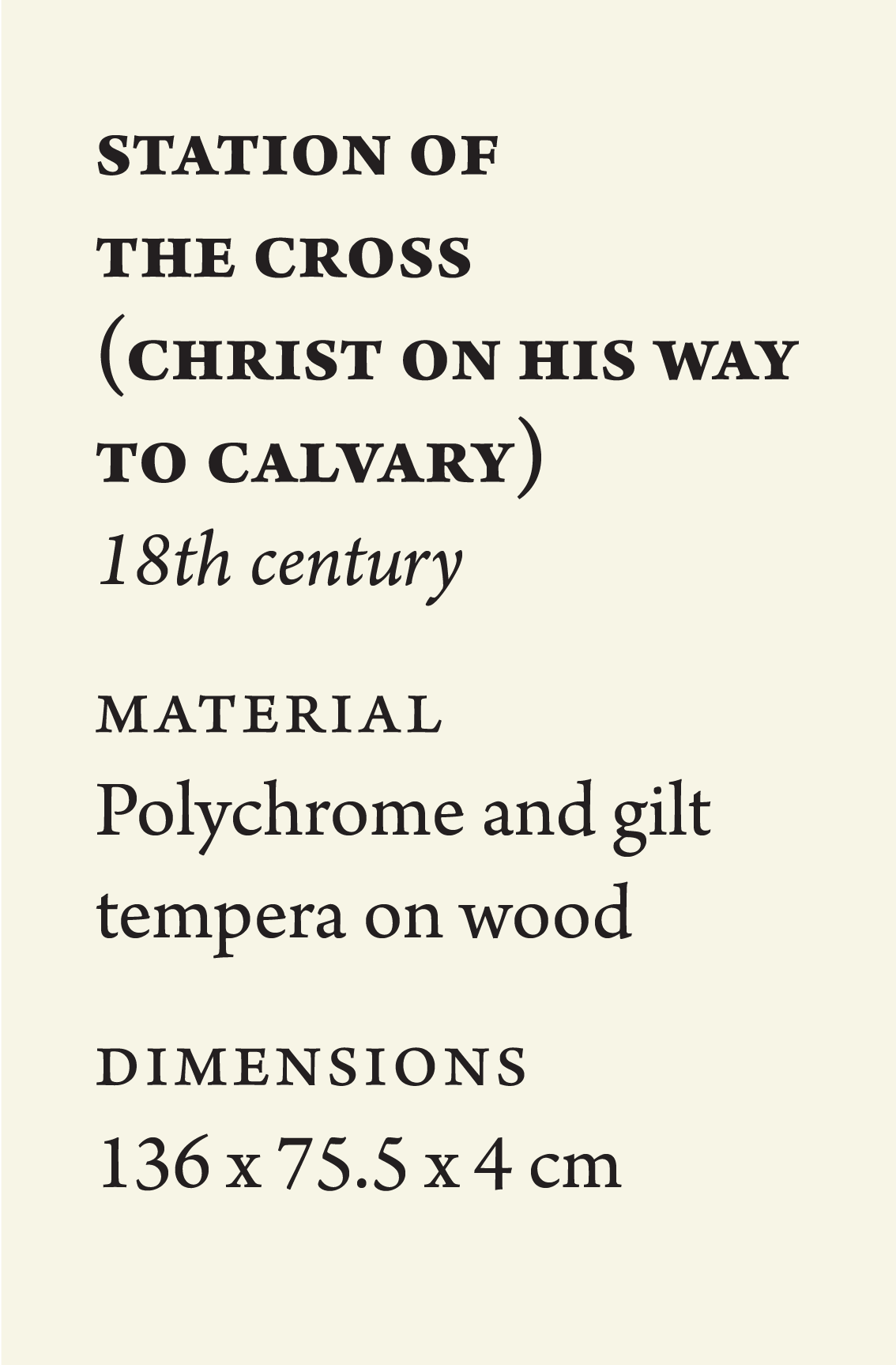

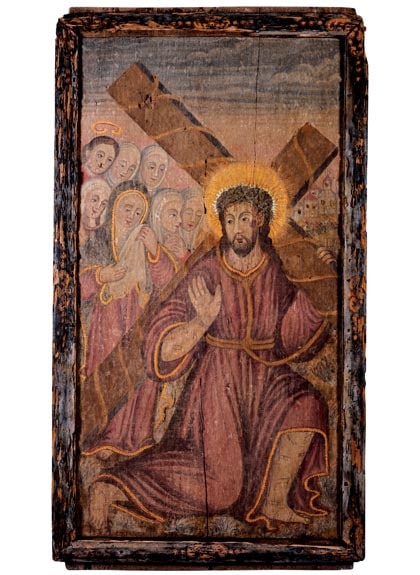

Then Jesus was given a large wooden cross by the soldiers, and so heavy was it, he had to drag it, bearing it on his shoulders, all the way to Calvary beyond the city gates, to his own crucifixion. And so he went, a lamb to the slaughter, and on his slow, painful way on the Via Dolorosa, he met many who mourned and walked with him: his broken-hearted mother, Mary, grieving disciple John, the weeping women of Jerusalem. Ignoring his own pain, he tried to console them all, telling them not to cry for him but for themselves and their children.

Christ carrying the cross to Calvary on the Via Dolorosa (in Latin, ‘path of sorrow’) was a very common subject in art. Although in early depictions the cross was not always represented as a heavy burden, by the later Middle Ages, it was shown as difficult to carry, to emphasize Christ’s suffering. From that period on, unlike earlier, he was also shown wearing his Crown of Thorns, as here. The most famous, and perhaps most beautiful, depiction of the subject from the Renaissance period was Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s large landscape entitled The Procession to Calvary (1564). Equally well-known is the painting by El Greco in his signature style, combining Byzantine, Renaissance and Mannerist elements, called Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1580).

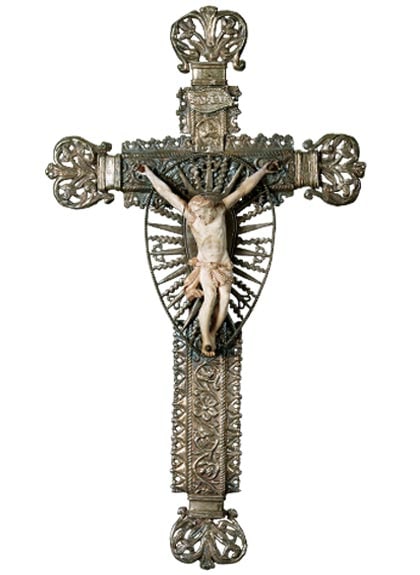

And among the lamenting women lining the Via Dolorosa was one moved to sympathy on seeing the weary Jesus, his face covered in sweat and blood. At once, Veronica, for that was her name, stepped forward to offer him her veil to wipe his face with. Jesus accepted her offering, wiped his face, and gave her veil back to her. And when she held it up to dry it, she was astonished to see an imprint of his face on her veil. All around her a murmur grew at this miraculous happening.

This event is celebrated as the sixth of fourteen Stations of the Cross marking Christ’s Passion. But there is no mention of it in the gospels, with the legend being recorded only in the 14th century. The saint’s name combined the Latin words vera (true) with icon (image), meaning ‘true image’. The Veil of Veronica is considered by some to be both prototype and justification of Christian art (given the injunction against image-making), being made by Christ himself, the incarnation of the unseen God. Thus images became a legitimate way of portraying the divine to the faithful, taking on special importance in the Counter-Reformation period.

Famous paintings on the subject include Saint Veronica in early Flemish style by Hans Memling (c. 1470), and Hieronymus Bosch’s The Carrying of the Cross (c. 1510) and Albrecht Dürer’s Veronica (1513), both in the Northern Renaissance style.

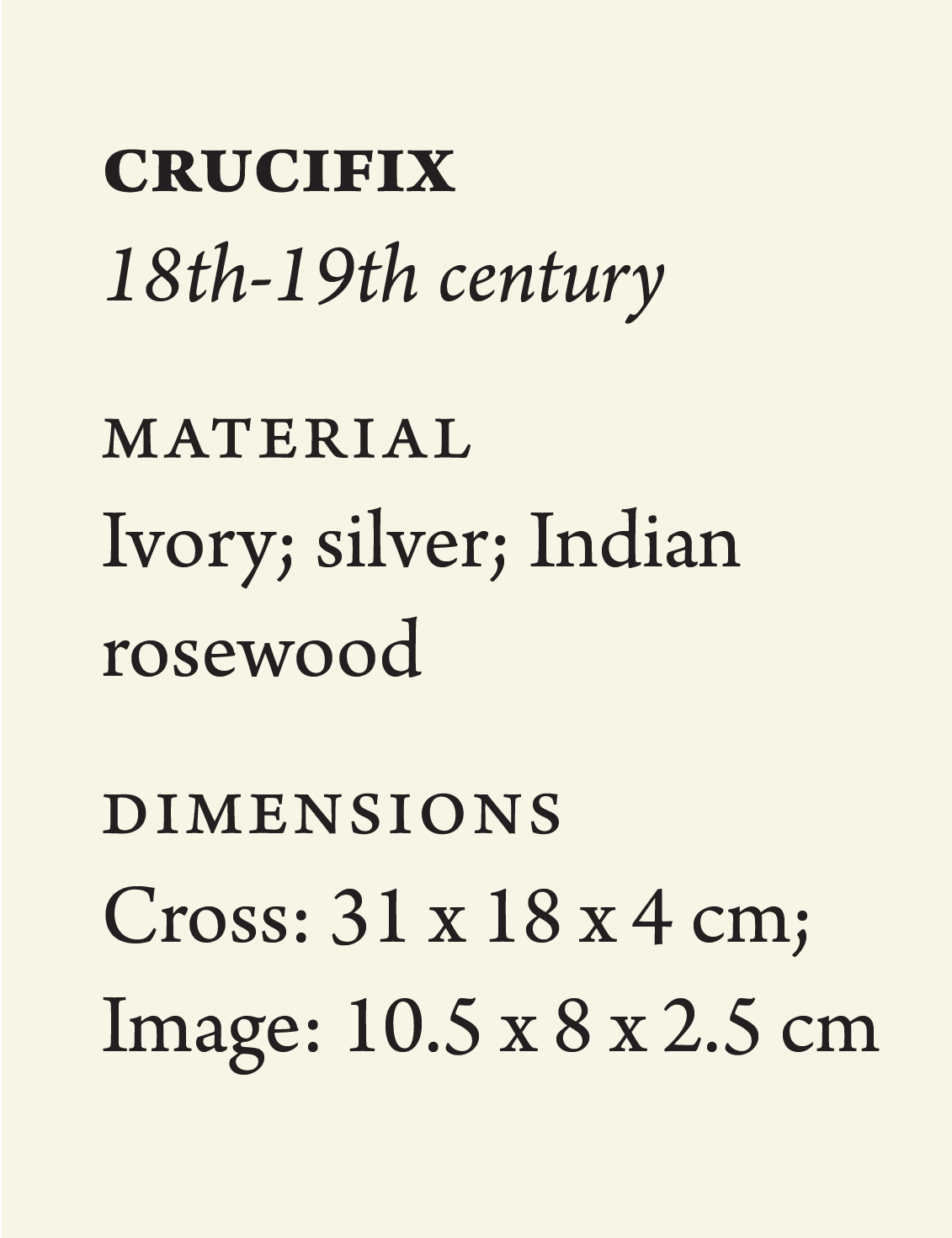

At last, Jesus came to Calvary, called also Golgotha, the place of the skulls, the end of his earthly journey. There he was stripped of his clothes but for a loincloth and nailed to the cross by the Roman soldiers. At the top they attached a sign that read ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’. ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do,’ Jesus said. Then, in great pain, he cried, ‘My god, my god, why have you forsaken me!’ Three hours later, ‘It is finished,’ he said.

It was before nightfall on a Friday, a few hours before the Jewish Sabbath. Jesus was between thirty-three and thirty-six years of age. His body was taken down from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea, who had asked for Pontius Pilate’s permission to bury him.

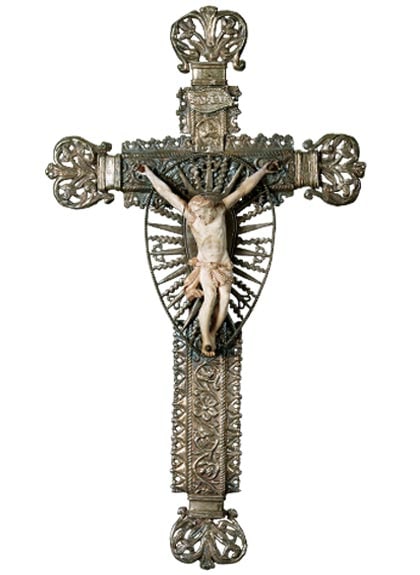

The Crucifixion was the subject of art as early as the 4th century CE. Famous paintings on the theme include Christ on the Cross by El Greco (c. 1590) in his characteristic style, the Spanish Baroque-style Cristo Crucificado by Diego Velázquez (1632) and, following in his footsteps, another painting of the same name by Francisco de Goya (1780), in similar style.

‘Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit,’ said Jesus with his dying breath. Then his poor, wounded body was brought down, and Nicodemus carefully extracted the nails so they could hurt him no more. His body was wrapped in spices and linen, and laid in a rock-hewn grave. But, lo! On the third day, when the grave was opened, the Saviour was gone, for he had been resurrected by his heavenly father. Forty days later, received by the kindly clouds, Christ Jesus ascended to heaven, his earthly task at end.

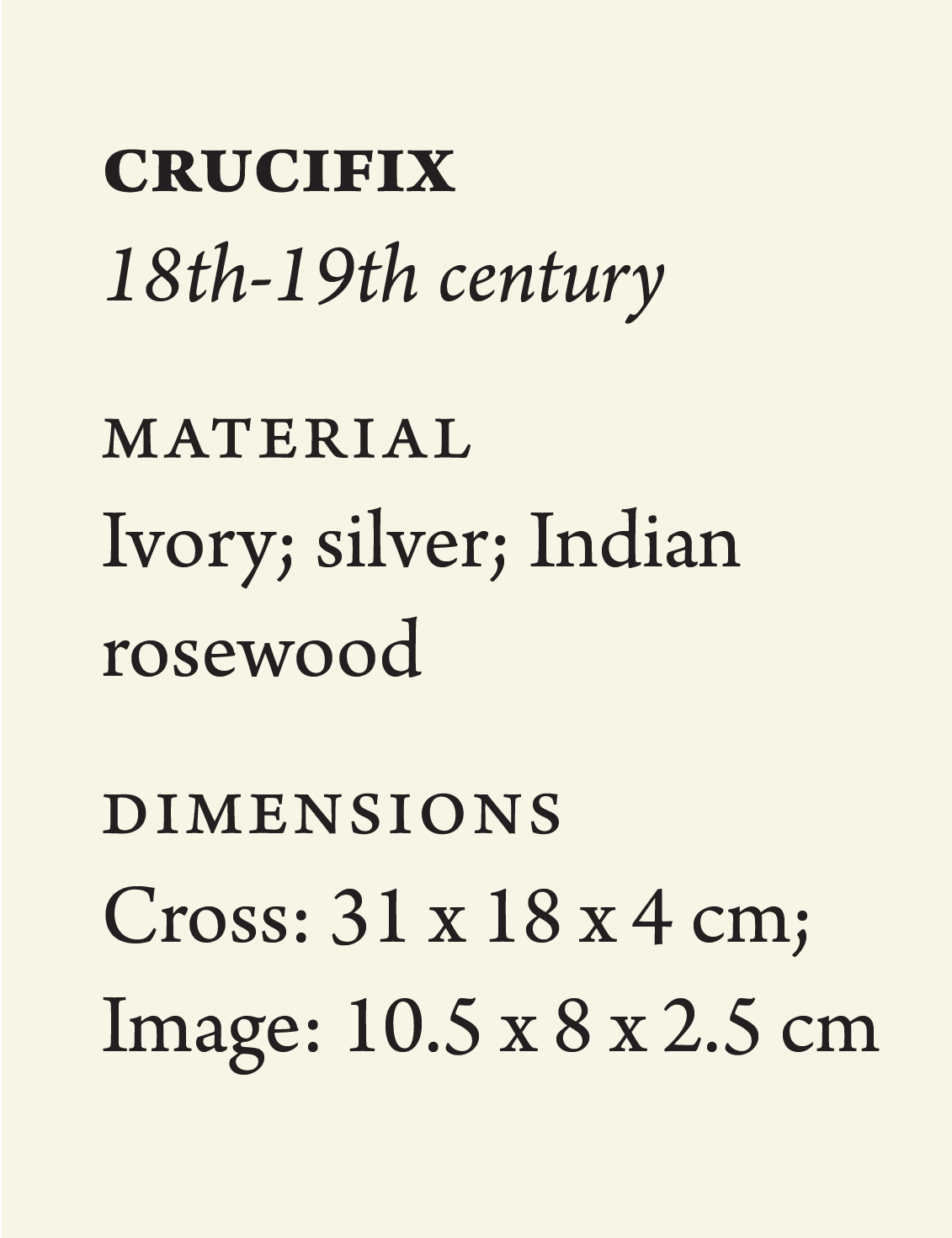

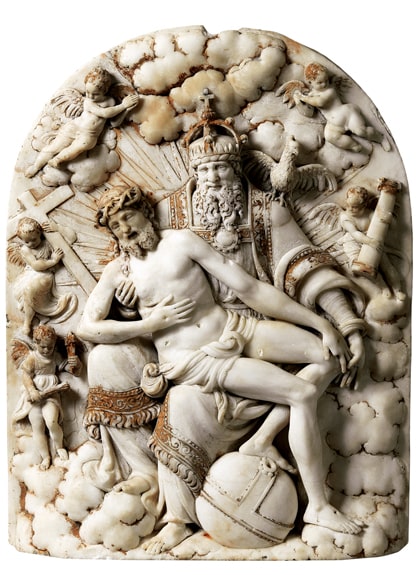

The Lamentation of Christ was a common subject in art, especially in sculpture, with one representation of it the pietà (in Italian, ‘pity’). Usually, it is Mother Mary who cradles her dead son before his entombment, the most famous example being Michelangelo’s Pietà in the Vatican. The early pietà was an artistic innovation from the Gothic period (12th century onwards), meant to humanize the divine and make people feel close to God. In this version, God the Father is shown as a sorrowful old man holding his dead son.

A large round Pietà (1400-10) by Dutch/French painter Jean Malouel in the early Renaissance period shows God the Father holding his crucified son, with a grieving Mary looking on. El Greco’s The Holy Trinity (1577-79) represents God the Father similarly, and is based on a 1511 woodcut of the same name by Northern Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer.