Above one of the two front doors of the imposing Church of Santa Monica, you will find a granite carving of a jaunty caravel with three square-masts, flags fluttering high and free in the wind. The caravel was a Portuguese sailing ship, small, swift and extraordinarily manoeuvrable, much favoured by explorers looking for the sea route to India.

That we see it here, intricately carved on the church’s facade, tells us how deeply symbolic it had become. At once, the caravel stood for the excitement of discovering a new route to India (spice-rich, and from antiquity a flame that burned in the European imagination), and the ambition of the Portuguese kings to conquer new lands and spread Christ’s word. It was also a symbol for the Church herself, that ship that carries the faithful across the ocean of life.

And what would have been on those flags the ship was flying? The armillary globe perhaps, a navigational instrument, but also the personal emblem of Dom Manuel I of Portugal (1495-1521), and a symbol for the world (sphera mundi) itself. More significant would have been the Cross of the Order of Christ (earlier the famed Knights Templar of the Crusades), the military order that helped finance the voyages of discovery.

In 1515, Pope Leo X instructed King Manuel to expand his kingdom over the seas, and spread the Good Word. The amazing success of the voyages of discovery made the maritime theme popular during this period (the Manueline) in architecture and art, even in devotional objects such as this incense-boat (in Latin, navicula or boat-shaped), made to look like a real ship.

It was common for European kings, including Roman emperors, to be represented holding a cross-topped globe to show their dominion over the earth. Much like these earthly rulers, the Infant Jesus here holds in his left hand an orb surmounted with a cross (globus cruciger). The orb, of course, signifies the world, and shows Christ’s rule over it. He is shown here as Salvator Mundi, or the Saviour of the World, a popular motif in art; the terrestrial globe he stands on is also customary. The motif of the globe was also common in Baroque art of 17th century Europe.

The journey by sea was long, hard and dangerous, and took as many as six to eight months. Travellers of all types had to face the perils of the deep, with some not knowing whether they would ever see home again. For ordinary people, perhaps the only relief was from a sailor singing the occasional plaintive sea shanty. Maybe it was Moorish in origin, full of loss and longing, leading in future centuries to the fado. Ecclesiastics, by contrast, when European but not Portuguese, spent this time learning the language to help them in their work in Goa.

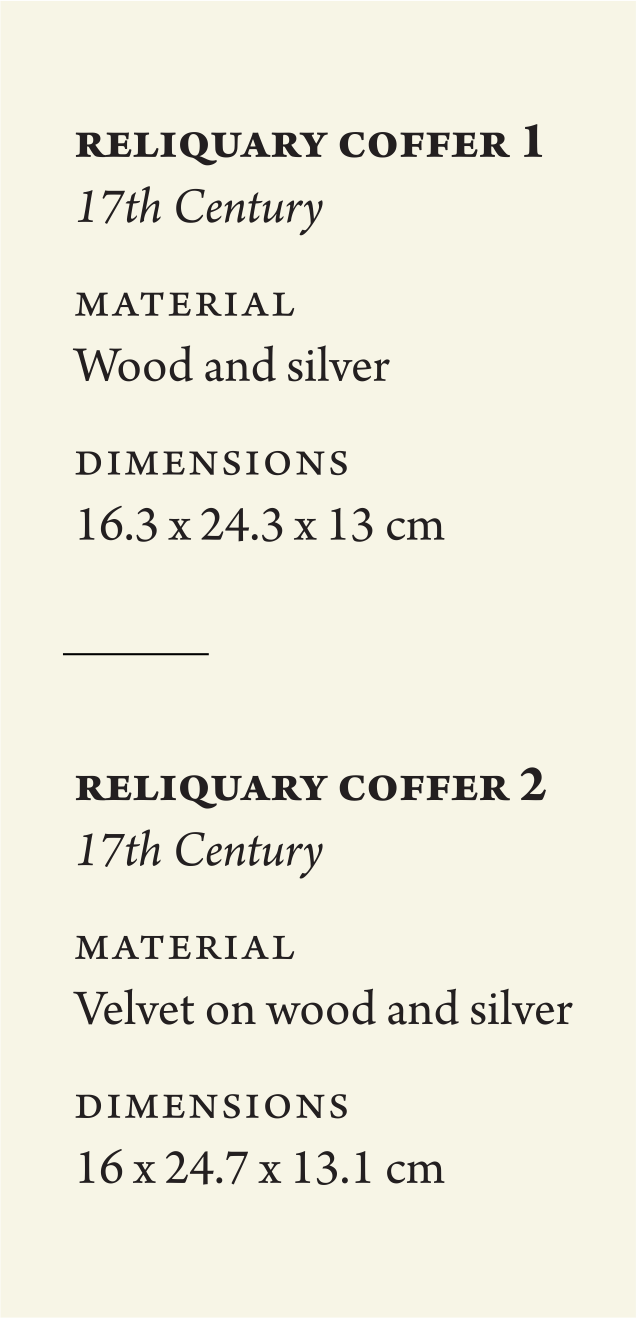

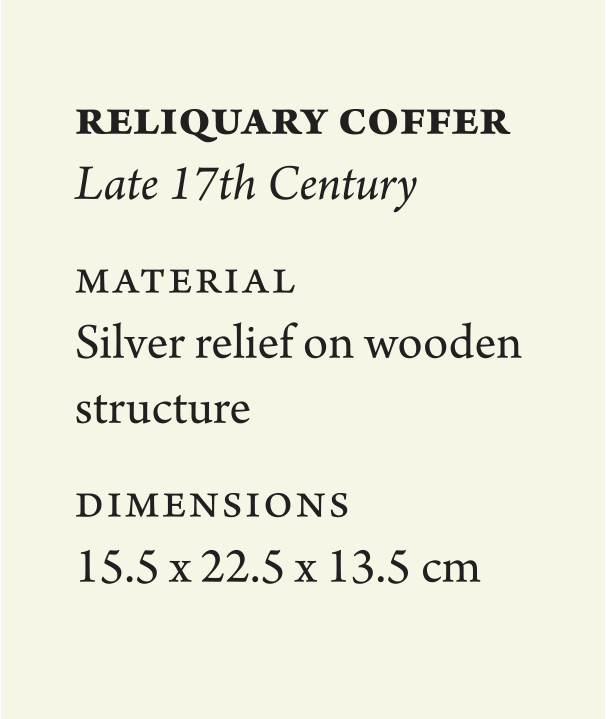

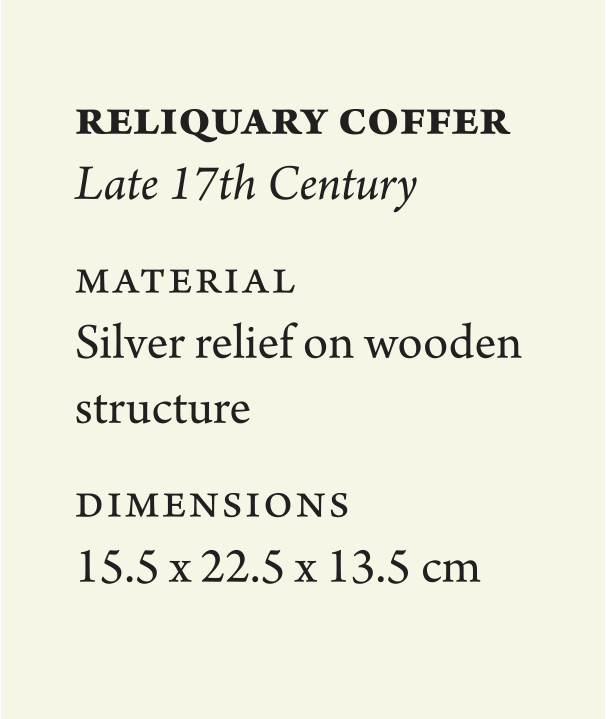

Whoever they were, the little they could carry with them was in transport chests like the ones these reliquaries are modelled on. On the way to Europe, such trunks would have held spices, especially pepper, sugar, textiles and jewels. On journeys east, some filled them with personal effects, others with religious materials.

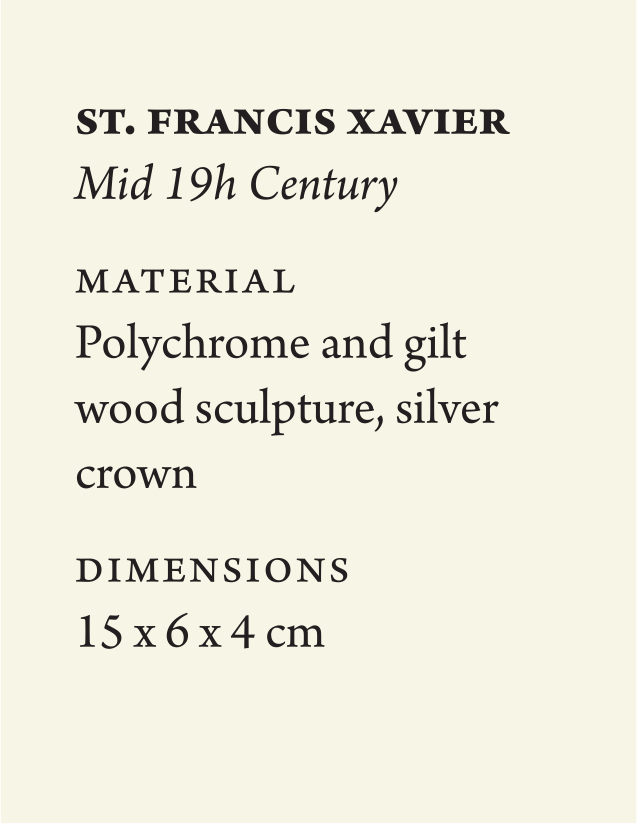

When Father Francis Xavier stepped off the ship at Goa in May 1542, he was thirty-six years old. He was there to represent both the Pope and the Portuguese crown, and seemed to embody the very spirit of the Counter-Reformation, a soldier of Christ. He was one of the first Jesuits, along with St. Ignatius Loyola, with whom he founded the Society of Jesus.

Devout, disciplined, passionate about spreading Christ’s word in the East, he was appalled by the decadence of Portuguese society in Goa. In a letter to Dom João III, King of Portugal, he wrote, ‘What is the profit of gaining the whole world and losing one’s soul?’ (Matt 16:26).

From a noble family himself of Navarre in Spain, and Basque by birth, Father Francis Xavier was filled with compassion for the poor, the ill, and the defenceless, and prepared to undergo any suffering on their behalf. In Goa, it was customary for the rich and powerful to never set foot on the ground but be carried everywhere by palanquin or sedan chair.

But when Father Francis stepped ashore in Goa, he ignored the splendid palanquin and retinue that waited to take him to the Viceroy’s palace. Paying no heed to his own comfort after the arduous journey, he instead hurried barefoot to a hospital for lepers. There, with great tenderness, he washed the sores of the afflicted, and tried to soothe their spirits.

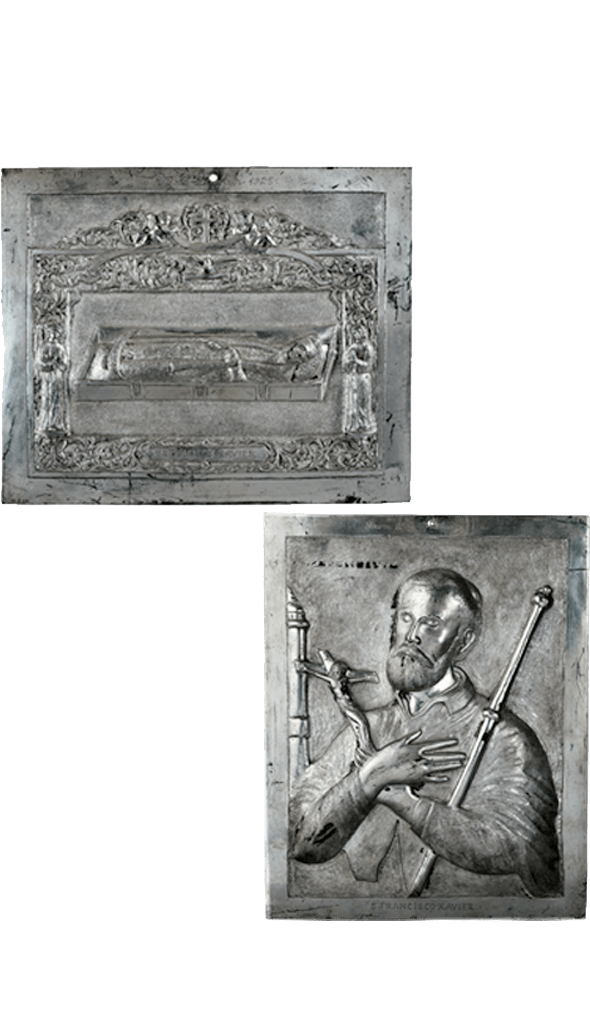

In 1545, Father Francis Xavier went to Malacca, in present-day Indonesia, to continue to spread Christ’s word. On 1st January 1546, he was on a ship that was to take him from the Isle of Amboyna to Seram. On the way, a huge storm brewed at sea, and the ship was about to be wrecked. At once, the mariners begged Father Francis to intercede. So he took his crucifix and held it high, taming the winds and causing the storm to die down. Suddenly, the vessel lurched, and his crucifix flew out of his hand and disappeared into the waters.

But when he arrived at Seram’s shore, a crab scuttled up to him, his crucifix in its claw. From then on, the crab became St. Francis’s attribute. It can be seen on this altar card dedicated to him, along with a hinge-shelled bivalve, continuing the marine imagery.

Once, Father Francis sailed to Cape Comorin at India’s southernmost tip to meet the pearl fishermen there. He spoke to them of Christ, but they were unmoved. Then he saw they were in mourning; one among them had died, and been buried the previous day. Father Francis said, ‘Bring him, and I will restore him to life.’ They did, and to their wonder, he prayed over the man, and raised him from the dead.

At another time, in Malacca, he met the vicar there, dying, and in despair of his soul, for he had not lived the good Christian life. Father Francis drove his demons away, heard his confession, and the vicar passed away in his arms, at last at peace. These two stories are depicted on this reliquary coffer of the saint’s, which contains a piece of his surplice. Is it fanciful to think it could be a part of the unusually grand surplice he wore to the prince of Bungo’s court in Kyushu, Japan, to impress him, and convince him of Christ’s word?

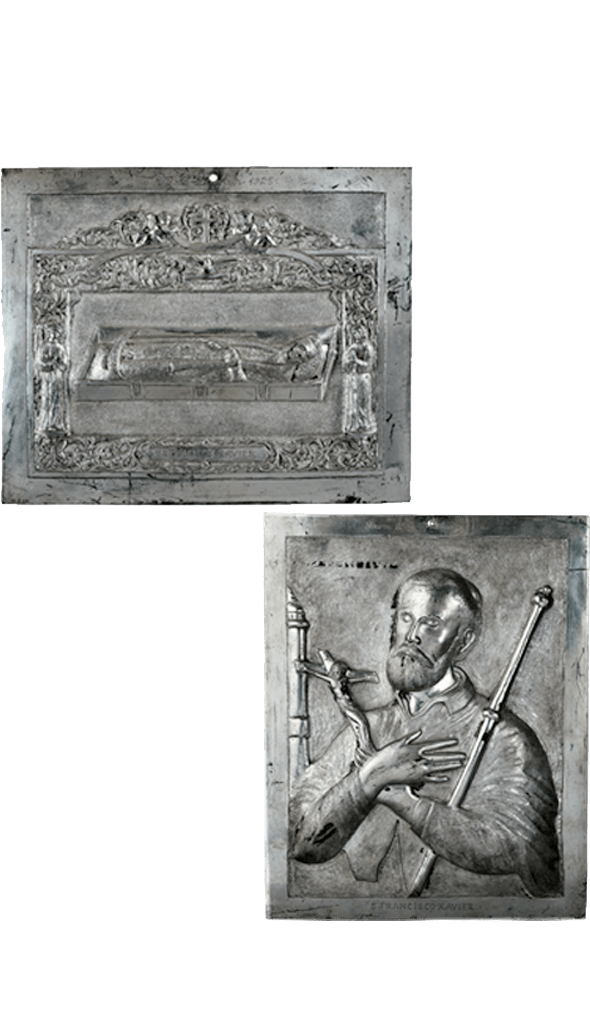

In late 1683, Sambhaji, the Maratha king, decided to storm Goa and seize the ports that were servicing the Mughals, their arch enemies, and allies of the Portuguese. The situation grew so grave that Viceroy Francisco de Tavora, Count of Alvor, rushed to the Basilica of Bom Jesus, where St. Francis Xavier’s casket lay. Having it opened, he placed his viceregal baton in the saint’s hand, handing over the territory symbolically to his care, and prayed to be saved from the Maratha attack.

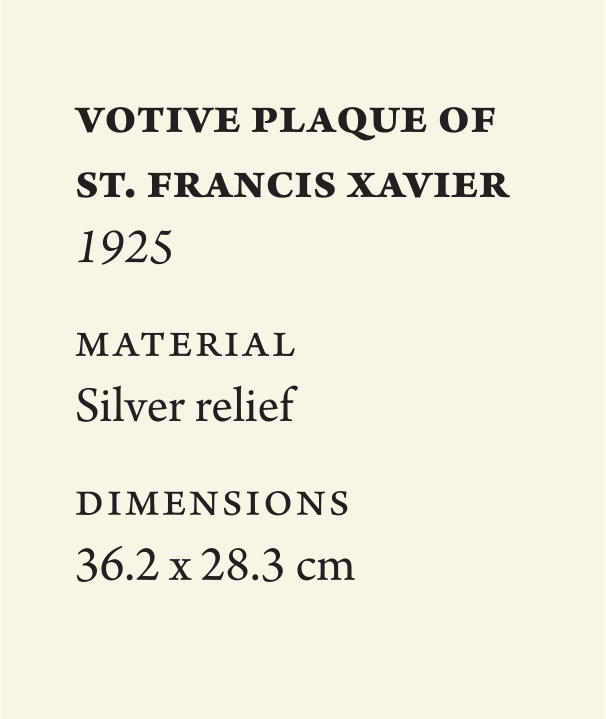

As it turned out, in January 1684, Sambhaji was forced to withdraw from Goa by the arrival of the Mughal army. This story is depicted on one of these two votive plaques dedicated to St. Francis Xavier, given in fulfilment of a vow or in thanksgiving. Both were donated in 1925, and by the same person, P. S. Dastur. Under what circumstances was she or he seeking the saint’s intercession or offering up thanks to him? We may never know.