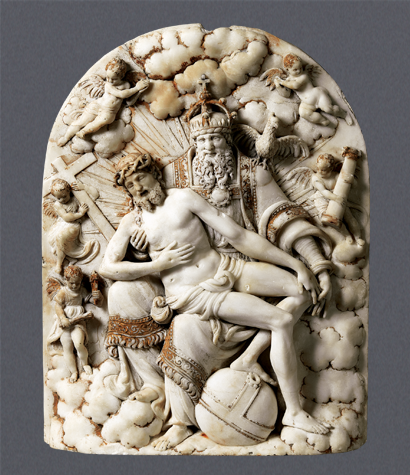

This small radiant ivory sculpture of Our Lady is perhaps the culmination of the composite Indo-Portuguese artistic tradition that evolved over four centuries. The Madonna is here the Nirmala Matha (‘immaculate mother’), as she is known in the vernacular, her pristine nature reflected in the ivory’s soft glow. The sculpture’s size indicates that it was an object of personal devotion.

Recalling the ivory sculpture style of early 20th-century Mysore, the artist also seems to have taken inspiration from the famous royal painter of Travancore, Raja Ravi Varma, known for his paintings of Hindu goddesses, of which among the first and most well known was that of Goddess Lakshmi. Like her, Nirmala Matha stands on a lotus pedestal, with an inverted lotus as base. She wears an Indian-style crown in the manner of a Hindu goddess, but also to identify her as Queen of Heaven, another title of the Madonna’s. Added to the crown is a halo customary in Madonna images, as is the crescent moon she stands on. The Matha is dressed like a Hindu goddess, with long wavy hair left loose, traditional south Indian bell-shaped jhumkis (hanging earrings) and bangles, the soft folds of her sari possessing the subtle glow of Mysore silk. Beneath, her bare feet are visible in Indian style. Her hands are folded in prayer, her head is slightly tilted, and her eyes have a calm, inward gaze. Around her is the traditional Indian-style aureole with a stylized pattern of conches, again connecting her to Goddess Lakshmi, but also to the Indo-Portuguese shell design. At the very top is the Holy Dove with its wings spread out, a symbol of the Matha’s immaculate nature.

The lotus, representing purity and divinity, was a favourite motif of Indian artists, and is associated with both Hinduism and Buddhism. The practice of representing deities on a lotus-seat or lotus-pedestal indicated that the feet of divine beings do not touch the earth. The inverted lotus was used in Buddhist sculpture to signify the Buddha’s nativity in Ashokan pillars of the 3rd century BCE.

NOTES

Raja Ravi Varma’s Lakshmi and Saraswati were painted in 1896. In 1894, he started his Lithographic Press in Bombay, and after 1906, prints of these two iconic paintings were the most produced, and grew very popular. While combining realism with scriptural accuracy, the Raja deliberately made his representations pan-Indian in identity as his own contribution to the country’s freedom struggle, a feeling perhaps shared by the present artist.

REFERENCES

Sihare, Manjari. “Raja Ravi Varma’s Oleographs: The Making of A National Identity,” The Saffron Art Blog, January 23, 2013. http://bit.ly/2QO5TlJ

PUBLICATIONS

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.