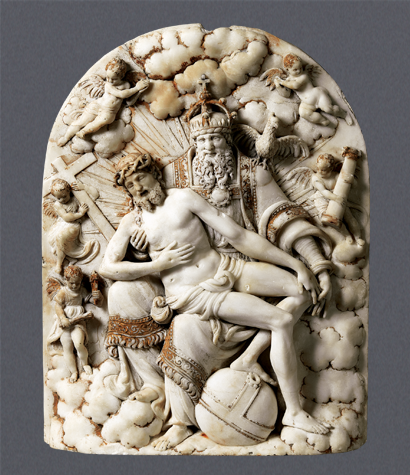

This large image of Saint Veronica, despite its dating, shows the influence of Flemish sculpture from the late 15th/early 16th century, and was perhaps modelled after such a piece. It was likely meant for personal devotions, and placed in a family oratory, passing down from generation to generation.

Flemish in the way the body is held, the drapery, positioning of veil and representation of Christ’s face, the fluidity of the clothing also shows Baroque influence, and reveals the skill of the Indian sculptor. Interestingly, the square shape of the saint’s face is matched by that of the Saviour’s, an unconscious artistic rendering that emphasizes her quality of empathy, also evident in the sweetness of her expression. While both faces, and the saint’s features, are European in colouring and aspect, Jesus’s are distinctly Levantine as they would originally have been. The saint has bluish-grey eyes and pink cheeks, Jesus’s downcast eyes are dark-brown, as are his curly hair and beard. On his head he has a Crown of Thorns.

The saint wears an orange-red robe, now brown with time, decorated with gold flowers only faintly visible. She is dressed, nun-like, with white coif, and blackish-purple mantle covering her head. Her eyes record the moment after Jesus gave her back her veil, having wiped his face with it, being pensive, sad, inward, as well as amazed at the miracle she has just witnessed: finding an imprint of his face on it. The whiteness of the veil sets off Christ’s face with carefully delineated hair and beard, downward gaze and remote expression. The saint’s body is held very naturally, with left leg angled slightly in.

The encounter between Veronica and Jesus on the Via Dolorosa, where she offered him her veil to wipe his face with, now celebrated as the Sixth Station of Cross, finds no mention in the gospels. The legend first appeared in 11th century Europe, being recorded only in 1380, in the popular Meditations on the Life of Christ. The saint’s name combines two Latin words, vera (true) and icon (image), meaning ‘true image’. The legend of St. Veronica gained further significance in the Counter-Reformation period as prototype and justification of Christian art.

PUBLICATIONS

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.