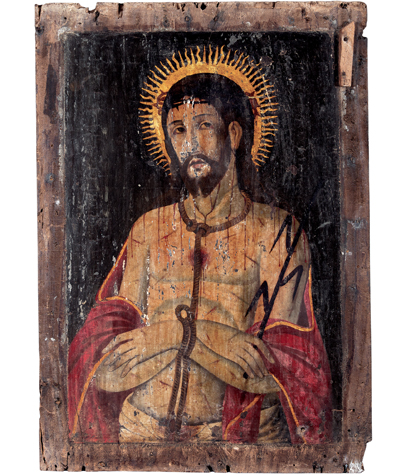

This evocative painting of the seventh Station of the Cross is Baroque in its realism and dramatic impact, and was perhaps modelled on a European print. But the Indian artist’s skill is evident in his understanding and presentation of the story so as to heighten the viewer’s emotional response.

The warm colours and fluid drapery are Baroque in style. Jesus is dressed in his customary purple robe that has turned brown with time, with the edges gilded to resemble embroidery. His face is European in aspect, and on his head is a stylized silver criss-crossing crown of thorns ending in silver tines, topped by a double halo, one of solid gold with radiating rays of pale brown over it. His expressive eyes reveal his pain and sorrow as he turns away from having just consoled his mother, disciple John, and the grieving women at the gates of Jerusalem. There are lacerations on hands and legs, and dramatic traces of blood on his face and neck. While the visible leg is not so well-proportioned, both feet and hands are Italianate in style, being slender and rounded. A realistically rendered brown rope is tied to his waist and neck, and around the cross. The cross he carries on his back is proportioned to fit the frame; its heaviness emphasizes Christ’s suffering, an artistic convention from the later Middle Ages. The inclusion of the Crown of Thorns is also from this time.

The Mother is in her customary scarlet robes, brown with time, and both robe and brown mantle covering her head are edged with the same gilded simulated embroidery as her son’s. The gold trim of the mantle doubles as a halo. She carries a white veil into which she weeps with great restraint. Identifiable by his halo, shaped like the symbol for eternity, is Jesus’s disciple St. John. The red of his robe remains, as also the red of the robe of one of the women, and some of the flowers in the middle ground. The Mother, St. John and the five women, perhaps including the ‘three Marys’ have faces Indian in aspect. The women, all with downcast faces, wear transparent white veils skilfully represented in light and shade; one in the foreground clasps her hands in sorrow. Stylized plants decorate the painting’s lower half. The gilded frame, not best preserved, is decorated with floral motifs.

Most interesting is a glimpse of Jerusalem and its buildings in the background, with a patch of flowers in front. Based on semi-stylized (combining real and imagined geography and architecture) renderings in medieval European maps, the earliest dating to the First Crusade, such artistic representations became a substitute for pilgrimage to the Holy Land, unthinkable for most, and a means to obtain indulgence for one’s sins. Here, the view of Jerusalem combines two different points in time: one, just before the Crucifixion, when the city is hostile to Jesus, and the other a symbolically Christian glimpse of the holy city allowing the viewer to participate in the Passion through art.

NOTES

Opinion is always divided about who the three Marys are but all four gospels mention a group of women disciples at the Crucifixion of Jesus. Other than Mary, the mother of Jesus, others variously identified include Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, Mary, mother of James, and even Salome, in this context called Mary Salome.

PUBLICATIONS

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.