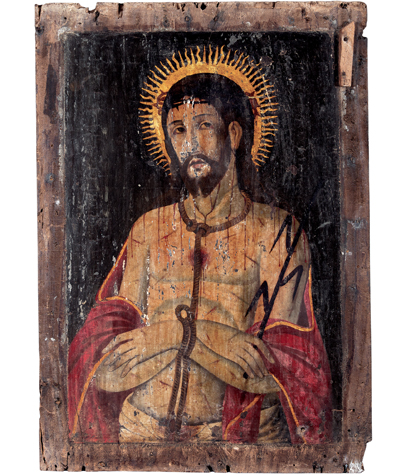

One of the highlights of the present collection, the Ecce Homo represents an early, significant moment in the Indo-Portuguese artistic conversation, and is justly worthy of study with regard to the achievement and intervention of the Indian artist.

The ‘Man of Sorrows’ or ‘King of the Jews’ theme, based on the Gospel of St. John (19: 4-5), took on renewed vigour during the Counter-Reformation period. A crucial scene in Christ’s Passion, it shows a bloodied, battered Christ emerging from the Roman hall of scourging, with crown of thorns, purple robe and reed-sceptre, all to mock him. He is then presented by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor, to the crowd, hoping for their pity, with the words “Ecce homo” (Behold the man!).

Christ is dressed in this polychrome gilded painting on wood in a gold-edged scarlet robe, his hands tied with a rope to his neck, and holding a once-green reed. Around his face is a dramatic radiating halo with straight and wavy rays in gold. His angular face and ascetic body are in European flesh tints, the body lacerated and blood-stained, the hands slender and rounded in the Italianate style. His hair and beard are in dark brown with the crown of thorns in a lighter shade; his expressive brown eyes hold both pain and detachment. His loincloth in white has both light and shade. The flesh tints use pigments similar to Iberian painting; the use of light and shade, and the transparency achieved, display European influence.

While the treatment of the body is in accordance with Spanish art treatises, the rich, warm colours and the intense gold effects, as in halo and drapery, achieved through gold leaf, are a specifically Indian contribution. The skill of the local artist is revealed in both style and rendition of the subject, and in his sense of story. He combines indigenous materials and artistic knowledge in the execution of his work, with the use of red and yellow ochre, and lampblack (local pigments), along with the unfamiliar verdigris. For the background, he chose lampblack, as Indian mural art practice stipulated, as against Portuguese boneblack, knowing the latter would cause efflorescence with time. Verdigris, on the other hand, a commonly used pigment in 17th century Portuguese painting, was unknown to him; the choice of this chemically unstable pigment has meant that the green reed has turned brown due to oxidation over time.

The original frame of the painting is missing, leaving the image free of visual constraint.

NOTES

For a detailed discussion of this painting with regard to layers, materials and methods, see Antunes V, Serrão V, Candeias A, et al. “Scrutinizing Ecce Homo: European or Indian painting? Assessment by Raman and complementary spectroscopic techniques” in Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2019, 50: 161–174.

REFERENCES

1. Serrão, Victor. “Painting and Devotion in Goa in the Time of the Philippians: The Monastery of Saint Monica on ‘Monte Santo’ (c. 1606-1639) and its Artists,” Oriente, No. 20, 2011.

2. Antunes V, Serrão V, Candeias A, et al. “Scrutinizing Ecce Homo: European or Indian painting? Assessment by Raman and complementary spectroscopic techniques” in Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2019, 50: 161–174.

PUBLICATIONS

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.