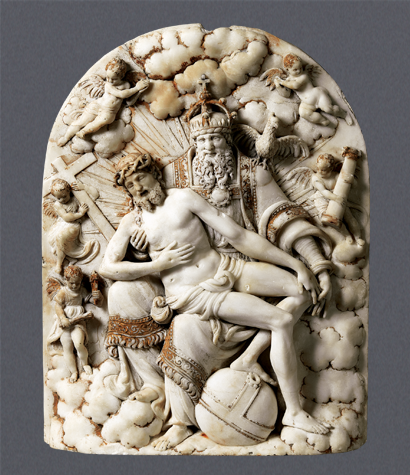

This arresting image of the Virgin in Majesty with the Child is a prime example of Indo-Portuguese sculpture, of which it was a favoured type of representation in the 17th century. The ‘Madonna Enthroned’ image dates to Byzantine times and became common in Europe during Medieval and Renaissance periods when the cult of the Virgin Mary was in ascendance. This particular statue was likely a hieratic object meant for a monastic community.

The Virgin is seated in an imposing 17th century-style throne whose back is topped by a semi-circular pediment with a simple design of a half-flower set within a half-flower; they look both like crown and halo. The back has a stylized lotus petal-like arch pattern all along the edges, and carries two simple floral motifs at front. One of the two original pinnacles remains, as also one of two original carved tassels. The Virgin’s pose is majestic, with legs curving slightly at the feet, while the arms are held in 17th-century style. Her missing right hand may have held a sceptre. In her left she holds the Child who stands on her knee. The Virgin’s seemingly disproportionately large head, the downward gaze of both Mother and Child, and the monumental size of the sculpture tell us that it was meant to be viewed from below.

The Mother is dressed in her customary red gown decorated with gold quatrefoils over which she wears a star-spangled blue mantle, which also covers her head, trimmed with gilt pearls typically Indo-Portuguese. Her feet are shod as is customary for this representation of the Virgin. The Child wears a short white gilt-edged tunic, right hand raised in benediction and left hand holding the sphere symbolizing the world. Both Mother and Child are Indian in aspect. The pedestal is plain, apart from the geometric design and diamond-point pattern, which confirm both date and origin.

The Romanesque (c. 1000 CE) ‘Throne of Wisdom’ (from Latin, sedes sapientiae) image with its Byzantine origins later evolved into the Gothic (12th century onwards) ‘Virgin in Majesty’ (from Italian, Maestà); in both, the Mother herself symbolically becomes a throne for the Child. The subject was common in sculpture and painting from this time onwards, and the present object with its characteristic features was likely based on 17th-century European models copied from prints.

PUBLICATIONS

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.