A spectacular example of Indo-Portuguese art, this tabernacle monstrance is made up of seemingly dissonant ideas that yet come together to make up an astonishingly beautiful whole. At over four and a half feet in height, it is easy to imagine the dramatic impact it had during Eucharistic celebrations.

The symbolic use of animals dates to Ezekiel in the Old Testament. The pelican had a significant place in this imagery, standing in for the Christ figure, as seen in Psalm 102: 7: ‘I am like unto the pelican’ (Similis factus sum pelicano). This way of representing Christ took on fresh resonance in the European Middle Ages, continuing right into the 17th and 18th centuries. The bird came to symbolize filial love, for the pelican was thought to open up its own chest with its beak in order to feed its young. In fact, when the pelican catches fish, it retains half-digested food in a throat pouch beneath its beak which is then fed to its young. In doing this, it appears to be wounding itself, parallelling Christ’s Passion, and the Eucharist.

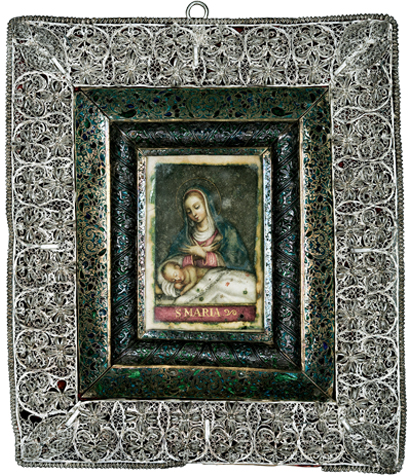

In the Goan context, although the pelican is indigenous to many parts of India, the artist was seemingly unaware of it. What we see here is his glorious interpretation of his commission in terms he understood. Going by head shape (but not comb or beak), body-, neck- and tail feathers, what we have here, in the main, is a peacock, of great significance in Hindu mythology, and associated with many different deities. This piece has two distinct but interlinked parts: a spherical base made of silver-covered wood, with a cavity for the tabernacle to which access is gained through an opening at the back; and the monstrance itself, a curious but artistically splendid amalgam of pelican and peacock. In its breast is an aperture surrounded by a golden sunburst halo designed to show off the consecrated Host for the adoration of the faithful. Two fledglings cling to the bird, waiting to be fed. The intricate silver plumage, powerful feet of silver-covered teak (?), monumental size and extraordinary creativity make this monstrance one of the best examples of the Indo-Portuguese artistic conversation.

Mumbai, CSMVS (with the British Museum, London and the National Museum, Delhi), ‘India and the World: A History in Nine Stories, 2017-18.

NOTES

This monstrance dates from c. 1630, was commissioned by Friar Diogo de Sant’Ana, and may have been crafted by a Goan silversmith, Jerónimo da Costa. See Victor Serrão, “Painting and Devotion in Goa in the Time of the Philippians: The Monastery of Saint Monica on ‘Monte Santo’ (c. 1606-1639) and its Artists,” Oriente, No. 20, 2011.

REFERENCES

Victor Serrão, “Painting and Devotion in Goa in the Time of the Philippians: The Monastery of Saint Monica on ‘Monte Santo’ (c. 1606-1639) and its Artists,” Oriente, No. 20, 2011.

PUBLICATIONS

Exhibition Catalogue, ‘Indian and the World: A History in Nine Stories,’ India, 2017-18.

Museum of Christian Art, Convent of Santa Monica, Goa, India, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, 2011.